Becoming The Brickyard

Search

Featured Article

Image of The Week

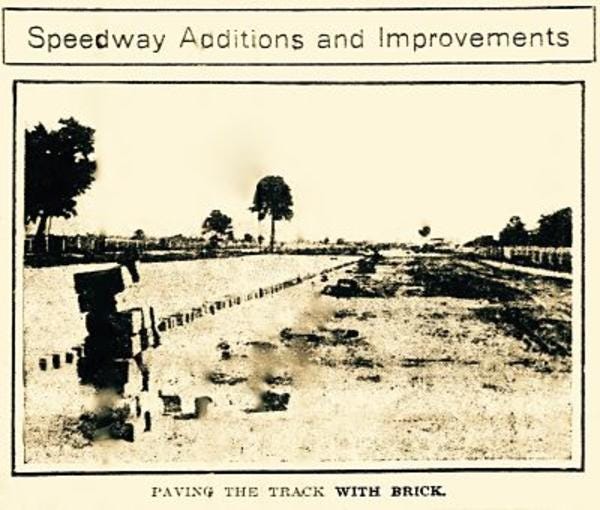

(Note — 109 years ago this month the Indianapolis Motor Speedway was undergoing a massive brick paving project.)

The bricklaying project that converted the Indianapolis Motor Speedway to the Brickyard is rarely discussed in any detail. The simplistic statement that the track founders paved the track with 3.2 million bricks after fatal accidents in the first race meet is insufficient nourishment for true historians and aficionados. The real meal comes with some juicy details.

Under fire from the Lieutenant Governor, members of the state legislature and Marion County Coroner John J. Blackwell who filed a scathing report finding negligence by track management, Speedway officials had to act. No action would almost certainly mean scuttling their investment or simply offering the grounds exclusively as a testing facility.

The original engineer of the track, Park Taliaferro Andrews, was called back from New York to oversee the paving project. The first challenge was to select paving material. Studying the world’s most successful example of Brooklands in England, the team’s first thoughts gravitated to a “bitu-mineral” solution. Essentially, concrete. This was also the choice of the Long Island Motor Parkway, a portion of which was in use for the Vanderbilt Cup.

Speedway Contest Director Ernie Moross was dispatched to Paris, Kentucky to assess a “bitulithic” manufacturing plant for purchase at $5,000. Obviously, Carl Fisher and his team thought a vertically integrated supply chain was attractive.

Meanwhile, another option was creosote wood blocks. This material was in use on the streets of metropolitan centers like St. Louis and had demonstrated durability and affordability. From Andrews’ perspective, the harsh Hoosier winters was a threat to concrete as expansion and contraction from temperature extremes would certainly generate cracks and the need for constant maintenance to avoid the kind of deterioration the track had experienced in the deadly August show.

Who knows what happened with the creosote block idea, but our guess is that the cost of acquisition was competitive while the long-term sustainability at the very least was suspect. It was one thing to endure the light traffic of city streets and quite another to withstand the pounding of giant race cars bounding along at speeds approaching 100 mph on the straights.

No spoiler alert here, the team landed on a brick solution. The best IMS enthusiasts know the supplier was Wabash Clay Company of Veedersburg, Indiana. They could not meet Fisher’s aggressive timeline of November 1, so they subcontracted to other brick companies as well.

A massive and labor-intensive bricklaying project ensued. The nearby train tracks were important as boxcars loaded with bricks parked outside the grounds and mules toting carts finished the delivery. Bricks were staged alongside the course as men with rakes and steamrollers graded the foundation surface.

Nobody knows for sure if it was a visiting local farmer or a newspaper writer who labeled the venue, “The Brickyard.” That person’s identity is lost to the ages. Yes, the track got its name before the paving began. It was more in reference to the stacks of bricks at the course’s edge all about the grounds than the finished product.

The timeline for project completion was driven by Fisher’s impatience — the same trait that pushed his team to present the excessively treacherous track conditions of August. It was the same reason he had to launch a National Balloon Championship race on June 5. His kinetic brain relentlessly fired ideas and his spirit demanded action.

Incredibly, Fisher and his team were still talking about grandiose race meets in October, including a “re-do” of the Wheeler-Schebler Trophy race that produced three deaths in August, and even more unfathomable, a 24-hour endurance race lit by Prest-O-Lite headlights mounted trackside. They also wanted an air show of airplanes and dirigibles.

This seeming insanity is a tunnel into Fisher’s personality. The man didn’t stop and never accepted that what he wanted wasn’t possible. Most of the time, that’s a good thing. Sometimes, if only rarely, it can mean disaster.

The realities of the project and the market (pulling together a critical mass of airplanes proved way too ambitious) soon proved the autumnal events were simply a bridge too far. The races were canceled before they gained any organizational momentum.

The bricks were tested by Art Newby’s National Motor Vehicle company. Wabash Clay assembled a test pad and the car company’s ace driver Johnny Aitken drove over it at speed, and, in the ultimate trial, did what almost certainly was the first Speedway burnouts.

Without meaningful brakes, this in-place grinding of the tires was done by sinking giant steel poles into deep holes filled with concrete and then connecting chains to the front and back of the National “Big Six” frame.

The results were convincing and the bricklaying began. As the fall race meets fell off the calendar, Fisher still wanted one, final, 1909 event. He looked to the last days leading up to Christmas. While at first, he wanted to sell tickets, unseasonably frigid weather convinced him and his team to just open the gates to anyone wandering in.

A handful of observers, typically hardy teenage boys, showed up along with newspaper writers and the teams. There was a ceremony featuring Governor Thomas Marshall — who later served under Woodrow Wilson as U.S. vice president — laying a “gold” brick as the finishing placement. The brick was actually the bronze material of track co-founder Frank Wheeler’s carburetor company.

Among the drivers on hand were Lewis Strang in his 200 HP Fiat, Walter Christie in his big front wheel drive “freak,” Johnny Aitken and Tom Kincaid in Nationals, “Farmer” Bill Endicott in a Cole, and Newell Motsinger in an Empire from a car company founded by…Carl Fisher.

An important fact obfuscated by time and the focus on safety is that Fisher wanted to lay claim that his speed plant was the “fastest speedway in the world.” Even Fisher had to grudgingly settle for America’s speediest race track as the high banks of Brooklands allowed flat out runs.

To this end, the December event was a time trial with drivers in different classes of cars vying for top honors in kilometer and mile runs. There was no purse, every competitor was a factory employee.

With temperatures well below freezing, drivers covered their faces with makeshift balaclavas, wore gloves, and warmed themselves by fire when not in the car. The first day was December 17 and produced record speeds by Strang and Christie.

Fisher wanted to go into the new year with the motoring trade papers summarizing events of 1909 and reporting that the fastest miles of the previous 12 months were achieved at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

The Speedway’s biggest American rival was the two-mile red clay oval of Atlanta — founded by Asa Candler of Coca-Cola. They would soon challenge the veracity of IMS claims, knowing the colorful promoter Moross had been the one on the watches.

Not that Moross, famous for ballyhooing and organizing Barney Oldfield’s barnstorming shows, wasn’t above embellishing the facts, but the new surface with the fast cars involved probably did deliver records. Like so many things historic, there is an admitted shadow of a doubt.

That’s just another colorful reality of the story behind the throwaway lines of much of history. Come to First Super Speedway and dig a little deeper. Get to know the characters, and understand their motivations. It’s all at your fingertips…if you click thru.

As for the image here, it’s a shot of bricks staged for placement on the freshly graded track foundation. Isn’t it a wonder?